Island of GreenA Canoe Trip into Quetico Park after the

Bird Lake Fire . . . The northern shore comes into view,

and we suddenly realize how devastating the Bird

Lake fire was. |

Maybe I'm too much of an optimist, but I still think that years from now, all three of us are going to smile when we look back to our summer trip of '96. After all, no one got hurt, we caught fish, and we had some nice private scenery for a few days. Heck, it didn't even rain - well maybe that was part of the problem.

In August of 1995, our family hosted a student from Japan through the American Field Service (AFS). His name is Naoyasu (now-yahs) and he grew up in the heart of Tokyo. After a year of hard work, learning English and pulling through his senior year at Eisenhower High School, I thought it would be great to take a trip to Quetico Park. I had visions of previous years-lazy sunny days, sitting by the fire, telling jokes in the evening and all of the other good things about a wilderness trip. I wanted to show Naoyasu what a great place we had just across the border.

I sent in my reservation for a park entry permit in January, and in March I went to a sports show in Milwaukee that many of the outfitters attend. As usual, Earl and Anita Cypher had their booth set up at the show for their outfitting business, Superior-North Canoe Outfitters. Their place is located at the end of the Gunflint Trail, about 55 miles west of Grand Marais, Minnesota. Earl is an easy-going guy that will listen for hours to your questions and patiently answer them. He runs a clean, efficient business, that you can't help but admire.

I knew that the Bird Lake fire of '95 blackened much of the area we would be in, but I wasn't sure exactly how it mapped out.

"Where was the fire?" I ask. Earl brings out a map and sketches in a huge area of forest. Starting at Bird Lake, the fire, fanned by a southwest wind, burned north past Kawa Bay on Lake Kawnipi, and east all the way to Saganagons. Our entry point to Quetico is right in the middle of the shore where the fire ended. Earl assures me that there are patches of green left, so it might not be too bad. Leaving the sports show, I'm beginning to think it might be interesting to see what the fire did. Earl also mentions that about nine feet of snow fell in the boundary waters area during the winter of '95/'96. That means that there should be plenty of water. We start drying food and getting ready. By the beginning of June, I can hardly wait.

After driving all day, we arrive at Earl's place at about five in the afternoon. Naoyasu and my son Mike unload the car and carry our gear into the bunkhouse. I go into Earl's office and settle up for renting an eighteen foot, three man canoe and for launching us through customs at the Canadian border. We'll be off Sunday morning, so we're in the sack early and try to get some sleep.

Now my first hint of trouble begins. Earl's bunkhouses are well constructed, but it seems as though more and more mosquitoes are finding some way in. I put on my head net and try to sleep, but Naoyasu is having a bad time of it. Never in a dozen years of sleeping in the bunkhouse was I bothered by mosquitoes, but that night they just seem to get worse. I finally hang our rain fly around Naoyasu's bunk and put on my gloves. Despite the rain fly, I keep hearing slapping sounds from Naoyasu's direction. Outside, the mosquitoes are swarming, finding any small crack and pushing their way in. Naoyasu finally asks me if he can sleep in the car. I don't blame him. The whining in my ears is keeping me up too.

Finally, I dig out our tent and string it between two of the bunk beds. We move two mattresses in and Naoyasu and I crawl in. I feel like a kid playing "tent" with the bed sheet, but we do end up getting some sleep. Mike does all right with just his head net. Now that I think of it, Mike can sleep through anything. He once slept through a crashing thunderstorm when we were camped on a small sand bar in the middle of the Wisconsin river. But that's another story.

The next morning all seems better. Earl loads

our canoe on one of his motor boats and we take off for

the Canadian customs station. Steve, who recently moved

to Grand Marais, and works for Earl off and on, is at the

throttle as we make our way down the long channel to Lake

Saganaga. The air seems sort of misty. When we reach the

customs station I ask Steve about it.

The next morning all seems better. Earl loads

our canoe on one of his motor boats and we take off for

the Canadian customs station. Steve, who recently moved

to Grand Marais, and works for Earl off and on, is at the

throttle as we make our way down the long channel to Lake

Saganaga. The air seems sort of misty. When we reach the

customs station I ask Steve about it.

"Smoke", he says. "There still are some fires south of here, but they are pretty far away." The smoke hangs like a light fog over the entire area.

Our next hint of trouble comes when the customs officer stamps our entry pass with a large red stamp: "NO OPEN FIRES PERMITTED". He tells us that there has been no rain for about six weeks, and the forest is tinder dry. Anyone caught building a fire may be ejected from the Park. I do have a small gas stove, and enough gas to last the week, but I wonder what we'll do in the evening to keep the mosquitoes away. As we get back into Earl's motor boat for the trip to the border, the customs agent hands us some mail for the Cache bay ranger station. Steve pulls the boat away from customs, and 20 minutes later we are at Hook Island on the Canadian border. We unload the boat, toss our gear on shore and wave good-bye. The mosquitoes are pretty bad so we quickly pack the canoe and shove off, going south to Cache Bay.

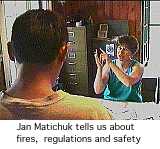

Our next stop is the ranger station. Jan

Matichuk, the ranger, again warns us about the fire ban,

and tells us about the existing fires that are smoking up

the Park. After buying our entry permits and fishing

licenses, I deliver her mail and we take off for Silver

Falls portage.

Our next stop is the ranger station. Jan

Matichuk, the ranger, again warns us about the fire ban,

and tells us about the existing fires that are smoking up

the Park. After buying our entry permits and fishing

licenses, I deliver her mail and we take off for Silver

Falls portage.

Things go fine during the day, but later that evening, the mosquitoes are terrible. With no fire to drive them away, we walk around in full mosquito armor - head net, gloves, long sleeve shirts and two pairs of socks. Sitting around the ring of rocks where a fire should be just doesn't cut it as an evening activity. We finally give up and get into the tent. The whine of the bugs is an all-pervading sound as we fall asleep.

There's no wind in the morning, so we get our full bug suit on before leaving the tent. Within an hour we've had our coffee and are on the water. An hour later, we round Boundary Point in Lake Saganagons. Our entry point for Quetico Park is just ahead.

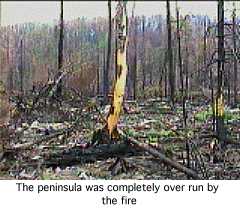

The northern shore comes into view, and we suddenly realize how devastating the Bird Lake fire was. There is a feeling you get when winter is coming; an empty feeling as the green goes out of the land, and you know that for a long time, the earth will be barren and cold. As we came close to the burned shore, this feeling crept into our canoe; we did not speak. Slowly and quietly, I steer the canoe along the shoreline of one of the islands near the park entry point. I expected black to color the land, but it is white rock that now dominates. Many trees are burned only slightly, but dead nonetheless, for the soil is all gone.

To break the spell, I suggest that we fish for a while. There are many trees that have burned at the roots and fallen into the water. Northern will lurk here, and it is not long before Naoyasu has one hooked and in the boat.

We pass another group of two canoes fishing near

the channel leading into Bitchu lake, and paddle slowly

into a haunting landscape. The shores, normally a lush

green, are now bare. Stark white rock covers the land, as

though the earth itself had died and left only it's bones

to bleach in the sun. Most trees are still standing, and

some have patches of green on their branches, but a

telltale black mark at the base of each trunk marks them

for death by starvation. We again fall silent as we drift

through the channel.

We pass another group of two canoes fishing near

the channel leading into Bitchu lake, and paddle slowly

into a haunting landscape. The shores, normally a lush

green, are now bare. Stark white rock covers the land, as

though the earth itself had died and left only it's bones

to bleach in the sun. Most trees are still standing, and

some have patches of green on their branches, but a

telltale black mark at the base of each trunk marks them

for death by starvation. We again fall silent as we drift

through the channel.

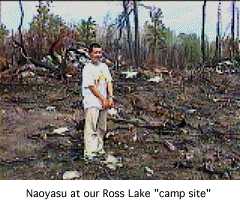

At the northwest end of Bitchu lake, we enter a shallow, marshy channel that winds and twists it's way to the next portage. With all of the burned trees in the water, I'm concerned that the channel may be blocked. We get through in about fifteen minutes however, and land at the portage into Ross lake. Normally, trees and brush surround you when you walk the portages. There is always the anticipation of the next few steps. Several times in the past I've surprised moose while portaging. Now the landscape is open and bare. It's odd to be able to see so far, and disturbing to not like what I see. Under our feet, a layer of fine gray ash replaces the mosses and pine needles that once covered the forest floor. It clings to our wet shoes and soils our packs as we unload the canoes. At the Ross lake side of the portage, we find all of the old bottles and cans that were left when the soil burned away. This portage is actually outside of the park boundary, and motor boats are often left here by people that fish the eastern part of Ross lake. The mosquitoes are not too bad now, so I dig out some cookies and cereal bars. I wonder what Naoyasu thinks about this trip so far. I expected to show him sunny breezy days and beautiful landscape. Instead, we are traveling deeper and deeper into a drought stricken ash pit. We paddle into Ross lake and turn west, crossing the boundary back into Quetico park.

My McKenzie maps don't show the campsites in Quetico, but in previous years I marked two sites on the southwestern part of Ross lake. We have no clue about where the first site was - the entire southern shore looks the same now. If a campsite existed, no trace of it remains. We pass a small, flat peninsula and head for the western shore. I've marked a campsite there in previous years, and we find the fire ring. Twisted, blackened trees lie across any flat area, and a fine coating of ash covers the ground. If we tried to camp here, we would end up filthy and miserable. Now we have a problem. Ahead lies the longest portage of the trip. We're tired and hot - I don't want to do another portage. I also don't know what lies ahead. I've only marked one campsite in Cullen lake, and that might be burned too.

We head back to the small peninsula and I jump out of the boat to look around. Near the eastern shore is a swampy area that has some thin grass. This area did not burn, and it's not too damp to put a tent on. On the southern part of the peninsula is a large rock next to the water. We should be able to cook and swim here without having to grovel in the ashes. We pull up the canoe, dig out our head nets and begin making camp.

The peninsula we are on was completely over run by the fire. I walk slowly through the thin layer of ash, trying to imagine what it was like on the day the fire came through. There are several trees that have tipped. One tree near the landing was growing in a thin layer of soil on top of a large flat rock surface. The tree was perhaps leaning slightly, and when the soil and roots burned, it simply fell over. Another tip-up near the center of the island lies with a pile of small bolders under it's roots. If wonder if the tree roots slowly broke up the rock below, for I do not see bolders except under the tipped up tree.

Many of the trees have no burn marks, except around the base of the trunk. The trees were green when the fire went through, and only the dead soil burned. Even if some of the tree roots were deep enough to escape the heat, the damage to the trunk base "girdled" the trees so that they could get no water or nutrients. They are brown and dead now.

Oddly, the fire skipped over a few areas, leaving some trees still green. I look across the water at the shore of Ross lake, noticing that there are a few green areas here and there. It seems that two things determined where the fire burned, and where it passed; the wind and the soil. If an area was sheltered from the southwest wind, the fire sometimes did not take hold. Unless the smoldering soil was fanned by the wind, it could not burn hot enough to engulf the living parts of the forest. I see an area of green with a tall, steep hill to the southwest. The hill kept the wind down and the fire passed around. There are a few swampy areas where the trees show no damage. With no soil "tinder" to catch the fire, these areas escaped completely.

An hour later, the two canoes that we saw at the park entrance come into view and begin circling the lake. Retracing our path, they end up coming back toward the island. I wave them in.

"This is it" I say as the canoes pull up. "We circled the lake too, and didn't find any place fit to camp." The four men come on shore and we introduce ourselves. They're from Minnesota, and are out on a 10 day trip. "There's room over there for your tent, and you can swim from this rock as soon as we're done." An hour later, after we are done cooking, our neighbors come over and we take a swim.

The next morning one of the men from the other group pulls a big northern into the shallows near our tents. Unwilling to get his feet wet, he attempts to drag the fish in, but it breaks the line and swims away. Soon our canoe is loaded and we say good-bye. Later we will know that they turned back east to get out of the burned area.

Our portage from Ross to Cullen lake is the

longest on our route. Fully loaded, it will take us 30

minutes to walk through. The three man aluminum canoe is

a load for one person, and with our radio, cameras and

fishing gear, we can't make the portage in one trip.

We're fresh, however, and it should be an easy walk. The

eastern end of the portage is in a swampy, shallow area.

We "pole" the canoe through a narrow channel

until we are stopped by a large waterlogged tree blocking

the path. I paddle us back to a soggy, mushy landing in

the swamp grass, and Mike and Naoyasu get out. For ten

minutes I try to slide the canoe over the log, but the

scratchy aluminum bottom is like sandpaper. I finally

paddle back, unload much of our gear, and then try again.

I get within 20 feet of the landing, and Mike and Naoyasu

drag me ashore with ropes.

Our portage from Ross to Cullen lake is the

longest on our route. Fully loaded, it will take us 30

minutes to walk through. The three man aluminum canoe is

a load for one person, and with our radio, cameras and

fishing gear, we can't make the portage in one trip.

We're fresh, however, and it should be an easy walk. The

eastern end of the portage is in a swampy, shallow area.

We "pole" the canoe through a narrow channel

until we are stopped by a large waterlogged tree blocking

the path. I paddle us back to a soggy, mushy landing in

the swamp grass, and Mike and Naoyasu get out. For ten

minutes I try to slide the canoe over the log, but the

scratchy aluminum bottom is like sandpaper. I finally

paddle back, unload much of our gear, and then try again.

I get within 20 feet of the landing, and Mike and Naoyasu

drag me ashore with ropes.

Now the sun is up, and the heat beats down on our swampy landing. I don't have a long sleeve shirt on, so I spray some repellent on my arms, load on a pack and start to walk. Twenty minutes later I come onto the scattered remains of a dead moose. The trail is covered with hair, and the skull, spine and several forelegs litter the path. I continue walking and soon reach the Cullen lake end of the portage. I've carried some water through, and now I drink deep and long. It's hot and buggy so I quickly start walking the path back east. An hour later, I arrive with the canoe.

We quickly load up and get on the water. After

only this one portage, my feet and legs look like I just

walked out of a swamp. I expected to spend two hours on

this portage, but with the downed tree and hauling our

gear through the swamp grass, the whole morning is gone.

We quickly load up and get on the water. After

only this one portage, my feet and legs look like I just

walked out of a swamp. I expected to spend two hours on

this portage, but with the downed tree and hauling our

gear through the swamp grass, the whole morning is gone.

We again survey the burned out shoreline as we travel through Cullen lake. As we go through the narrows on the east side, however, we suddenly see green. Hills on the southern side of the lake have evidently protected a patch of forest from the fire. The green forest is a welcome sight after last night's stay on the burned out island. I begin to think now of what lies ahead. The portage to Mack lake is just ahead. This portage ends in a shallow swampy landing. The transition from solid land to water is gradual. When the water is low, the landing on the Mack lake side is not too bad. You can walk to within 30 feet of the water and balance on stumps or logs while you load your canoe. With high water, the way it is now, the landing becomes is a bit more challenging.

A few years back I took this portage with my daughter Diana and her friend Karen. As the landing came up, the path changed from rocks and mud to just mud. I was bringing the canoe on the first trip through, and found that the only firm footing was next to trees or logs that had fallen. Concentrating on my feet, I suddenly came upon Karen. She had missed a step on a log and her leg sunk in up to her hip. I put down the canoe and helped her pull herself out. Twenty five yards of balancing brought us to a spot where I figured I could float the canoe. It took us a half hour to bring our gear through the mucky landing and get the canoe loaded.

I enjoy the hardship and physical labor that are sometimes necessary in Quetico. This isn't just my vacation, however, and a mosquito infested, nightmare portage landing is not what I had in mind for Naoyasu and Mike.

We round a point on Cullen lake and I see green to the north and east. I turn toward the green, and we find a large bay only slightly touched by the fire. A small peninsula juts out of the eastern shore. There is good exposure to the southern wind - maybe enough to keep the bugs away. As we paddle past the peninsula we startle a moose cow and calf on the northern shore. They quickly run out of the water and head into the forest. We land the canoe near the peninsula and I walk onto the shore.

Behind us there is only desolation: ash, twisted trees and the dead moose. Ahead is a portage that will sap the rest of our strength and will. Perhaps there is a usable campsite on Mack lake, perhaps not. Here in this small bay is an island of green, a small part of forest that brings peace to our eyes. Our trip will end here; we will travel no further. We unload the canoe and begin to set up our camp.

This small finger of land was cleared of brush

not long ago. All of the small trees and bushes that were

once growing are now piled at the edge of the forest, out

of the wind. I think that someone cleared the land here

so that the fire would not jump to the northern shore. If

that is what happened, it looks like it worked. I'm a

little worried, though by the large dry pile of brush and

trees that now are piled over six feet high next to our

tent. We must be very careful with our small gas stove to

prevent any new fire. I decide that we will cook on the

rocks right next to the water.

This small finger of land was cleared of brush

not long ago. All of the small trees and bushes that were

once growing are now piled at the edge of the forest, out

of the wind. I think that someone cleared the land here

so that the fire would not jump to the northern shore. If

that is what happened, it looks like it worked. I'm a

little worried, though by the large dry pile of brush and

trees that now are piled over six feet high next to our

tent. We must be very careful with our small gas stove to

prevent any new fire. I decide that we will cook on the

rocks right next to the water.

Later that day we fish. Mike pulls in a northern, and I land a walleye while trolling with a crank bait. I turn over the canoe for a table and within an hour we are feasting.

I really miss having a fire now. As the sun drops lower in the sky, the bugs start their attacks. I try to think back over the dozen or so trips I've made into the boundary waters, and cannot remember the mosquitoes being this bad. The odd part is that there has been no rain for six weeks. I can only guess that the nine feet of snow that Earl Cypher told me about has filled up inland ponds where the pests breed.

We are back to head nets and gloves. With no

fire, it seems pointless to sit outside. We retire early,

listening to the miniature buzz saws that drone around

the tent. To be outside without protection would surely

drive a man mad within an hour.

We are back to head nets and gloves. With no

fire, it seems pointless to sit outside. We retire early,

listening to the miniature buzz saws that drone around

the tent. To be outside without protection would surely

drive a man mad within an hour.

We spend another day on our island of green. Naoyasu swims and later we catch some fish for dinner. I feel little inclination to go exploring.

We pack up and leave the next day. Again we are in full bug armor. Ten minutes into the Cullen-Ross portage, we stop at the site of the dead moose. All three of us are wearing long sleeve shirts, long pants, gloves and head nets. As the heat beats down, swarms of mosquitoes circle our heads. We're hauling heavy packs over rough terrain and there's twenty minutes to go before we can wade through swamp grass and load the canoe. As we look at the pile of bones and hair, we joke with Naoyasu.

"When you get back to Japan, Naoyasu, you can tell all of your friends about the wonderful time you had on this trip!" Naoyasu smiles.

"AFS is a good experience" he says. We all start laughing.

We bypass the swampy landing at Ross lake and

load our canoe from a hump of grass next to the channel.

We paddle through Ross and quickly portage to Bitchu.

Within an hour, we emerge from the fire zone and our eyes

are treated to a horizon of endless green. Now each place

we pass triggers a memory. We pass the small island in

Saganagons where I made contact with a new radio amateur

on a stormy night. We pass the old hollow tree that

"sang" in the wind when I strung my antenna to

one of its' branches. We pass the nearly invisible

opening that we took one year to reach Bell lake. We pass

the worn out island near Cache bay where my brother and I

managed to build a fire after a full day of rain.

We bypass the swampy landing at Ross lake and

load our canoe from a hump of grass next to the channel.

We paddle through Ross and quickly portage to Bitchu.

Within an hour, we emerge from the fire zone and our eyes

are treated to a horizon of endless green. Now each place

we pass triggers a memory. We pass the small island in

Saganagons where I made contact with a new radio amateur

on a stormy night. We pass the old hollow tree that

"sang" in the wind when I strung my antenna to

one of its' branches. We pass the nearly invisible

opening that we took one year to reach Bell lake. We pass

the worn out island near Cache bay where my brother and I

managed to build a fire after a full day of rain.

That night we camp on an island in Saganaga. There is a breeze on the open waters, and for once we have relief from the mosquitoes. We paddle in the next day and by late afternoon we're checked into the old wing of the East Bay Hotel in Grand Marais.

I'm disappointed that we didn't make the full trip through the Wawiag river, Kawnipi and the falls chain. I know that we could have done it, but I don't think we would have enjoyed the scenery. Many people say that fire is a good thing - it renews the land and allows new growth and variety. If I knew that I would live another fifty years, I might agree, but in my limited lifetime, a large part of my world is gone. I will watch it come back, and remember it as it once was.

Copyright 1997 by James A. Hegyi

Return

to the Canoe Stories Index

http://www.canoestories.com/fire.html